The East-West antagonism was a defining dichotomy for a generation of artists who experienced the disintegration of Yugoslavia and later became associated with “East Art”[1]. This politicised curatorial framing accentuated the resentment felt by artists from the former East and favoured those artistic practices that put forth the inner conflicts, political tensions, and wars they experienced during the transition to capitalism. These artists were able to enter Western art institutions if they accepted and reproduced their own exoticisation and othering – a relation that became the operational model: both a coping mechanism and a token of entry.

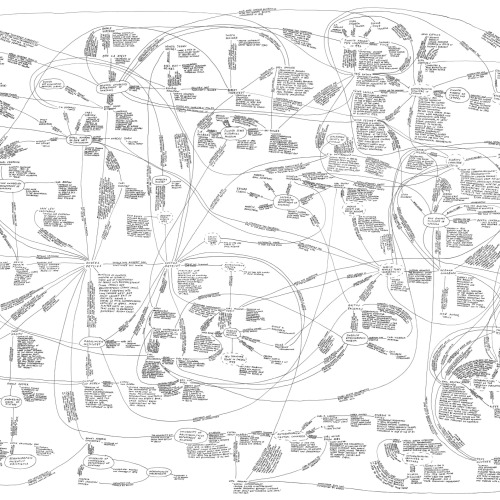

Starting in the 1990s and continuing well into the 2000s, this trend defined more than one generation of artists. In the late 2000s, the North-South dichotomy was added to the East-West divide. In Slovenia, interest in presenting art from or about the global South, and art created by the Southern artistic diaspora in the North, has since continued to grow.[2] In 2015, Lilijana Stepančič wrote that this interest was revived by observing recent exhibition practices of Western art institutions, not by continuing the cultural exchanges from the Non-Aligned Movement (NAM).[3] Still, new connections arose (at least) from encounters between South American and former Yugoslavian art contexts. It wasn’t until the Southern Constellations: The Poetics of the Non-Aligned (2019) exhibition in the Museum of Contemporary Art Metelkova that the cultural connections forged within NAM, which transgressed the East-West axis, were explored in Slovenia for the first time after the dissolution of Yugoslavia and the end of Slovenia’s non-alignment. This gradual reintroduction of the South-North dichotomy complicated the discourses and relations in Southeast Europe (SEE): it opened new ways of imagining what the decolonialisation of the SEE would mean from the perspective of the arts.

In the postcolonial world, racial hierarchies reified through the colonial legacy of scientific racism continue to reign supreme. If coloniality is a mode of thinking that reproduces racial and other hierarchies, produced and/or exacerbated by colonialism, decoloniality would indicate moving beyond the paradigms of global patriarchal colonialism and its close intertwinement with modernity. As such, decolonisation is a call for questioning the ways in which knowledge, heritage and memory have been reproducing colonial and patriarchal values and enabling the endurance of hierarchies. It is a call for reimagining the world as we see it. However, a decolonial stance cannot be de-territorialised, abstracted from a specific context or universalised. On the contrary, it needs to be localised – especially in countries such as Slovenia that fail to recognise their embeddedness in the colonial past exemplified by their participation in the global colonial trade of goods, people and ideas, and their embracing of racial hierarchies.[4]

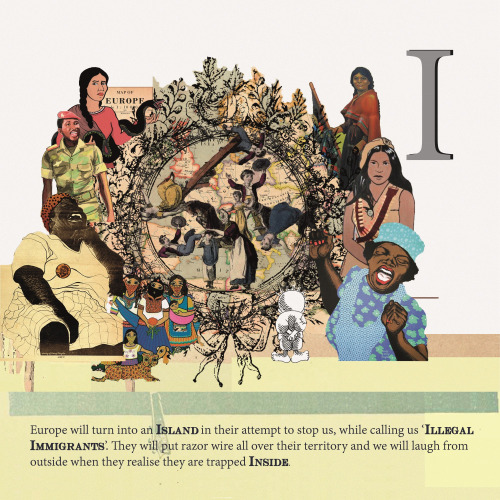

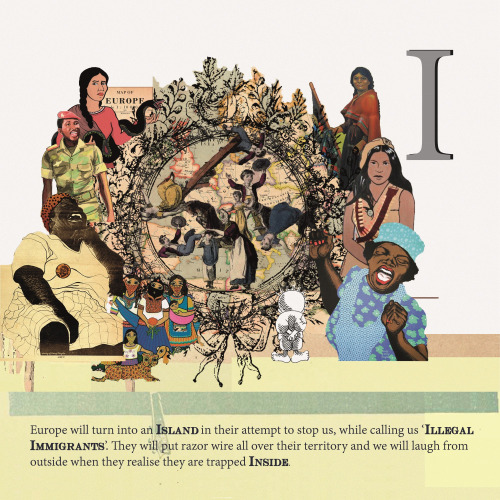

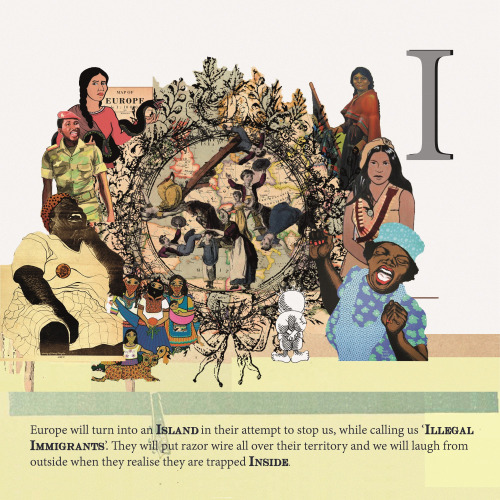

The South in Us exhibition looks at artworks and/as ideas that consider the historical and contemporary embeddedness of Slovenia and its neighbouring countries in global history in which, on the one hand, the SEE countries and their people have been racialised as the European Other while, on the other, coloniality left a strong mark in views on racial hierarchies as much as anywhere else. Until recently, race as the dominant term for analysing relations between colonising and colonised societies was not considered to be a relevant perspective for the study of territories that Slovenia historically constituted[5]. However, as Cedric J. Robinson writes: “Racism […] was not simply a convention for ordering the relations of European to non-European peoples but has its genesis in the ‘internal’ relations of European peoples.”[6] To this day, those “internal relations” consist of Western othering of the East, experienced by many people of the SEE diaspora who nevertheless often strongly self-identify with European whiteness and its racisms.

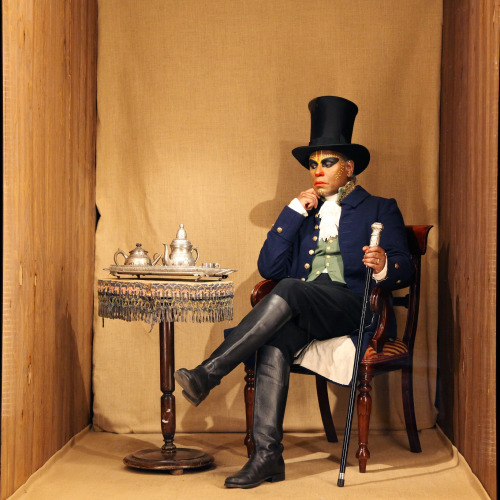

The artistic research included in the international group exhibition on three locations, the two opening performances by Minna Henriksson and George Chakravarthi, the discursive programme conceived in collaboration with Tea Hvala, and the dance performance by Christian Guerematchi look at the othering of the semi-periphery by the centre and the othering of other Others by the semi-periphery. The constant shifting between this overarching theme and specific individual artistic practices has brought to light the focus on Slovenia’s past inclusion in different multi-ethnic state formations and its influence on our contemporaneity (the Othering (in) the Semi-periphery exhibition at Škuc Gallery), the Yugoslavian experience of non-alignment (the NAM exhibition at Mala galerija) and the artificiality of the category of race as an idea and the basis for racism (the Constructing and Performing Ideology exhibition at Alkatraz Gallery).

The exhibition title The South in Us challenges the East-West divide by playing with the platitude that connects the economic underdevelopment of the South with the self-righteousness of the North. Južnjaki [“Southerners”] as a derogatory Slovenian term for immigrants from other former Yugoslavian republics resonates with people as we travel up and down the meridian[7]: its omnipresence implies that everyone has their Southerners and everyone is someone else’s Southerner. The South in Us exhibition is an attempt to think and act from this position of difference, all the while staying aware of the greater structural inequality of those who come from further East or South, thus affirming the City of Women’s mission: not as a corrective to the cannon but as a quest to find allies for structuring the world differently – together. Or, to paraphrase Gloria Anzaldúa: those who don’t become overwhelmed by their suffering will be better equipped to observe the inequalities around them.[8]

Iva Kovač

[1] In Slovenia, the term “East Art” was epitomised by MG+MSUM’s collection Arteast 2000+ and the East Art Map, a project mapping contemporary Eastern European artists initiated by the IRWIN art collective.

[2] For example, the 2009 City of Women festival, curated by Mara Vujić, focused on the Global South.

[3] Stepančič, Lilijana. 2015. “Pionirski časi: osebni spomini na prvi festival Mesto žensk”. In: Časopis za kritiko znanosti, domišljijo in novo antropologijo, v. 43, nr. 261, pp. 23–39.

[4] For some nascent research on this topic, see Mesarič, Andreja. 2022. “Racialized Performance and the Construction of Slovene Whiteness”. In: Staged Otherness: Ethnic Shows in Central and Eastern Europe, 1850–1939, Dagnosław Demski and Dominika Czarnecka (eds.). Budapest, Vienna, New York: Central European University Press, pp. 257–293.

[5] Baker, Catherine. 2018. Race and the Yugoslav Region: Postsocialist, Post-conflict, Postcolonial? Manchester: Manchester University Press.

[6] Robinson, Cedric J. 2000. [1983]. Black Marxism: The Making of the Black Radical Tradition. Chapel Hill, N.C.: The University of North Carolina Press, p. 2.

[7] Amjahid, Mohamed. 2020. “Seehofer entscheidet immer wieder, mit seinen Worten Menschen bewusst auszuschließen”. Der Spiegel, 13. 7. 2020. Available here [13. 9. 2022].

[8] Anzaldúa, Gloria E. 1987. Borderlands/La Frontera: The New Mestiza. San Francisco: Aunt Lute Books.