The Clitoris as the Starting Point for the Dialogism of Feminist Movements

The starting point of this article is Catherine Malabou’s lecture The Clitoris is an Anarchist, which she gave at the 29th City of Women festival. Since she opened the space for a discussion on the different waves of feminism, we will continue with the same subject matter.”

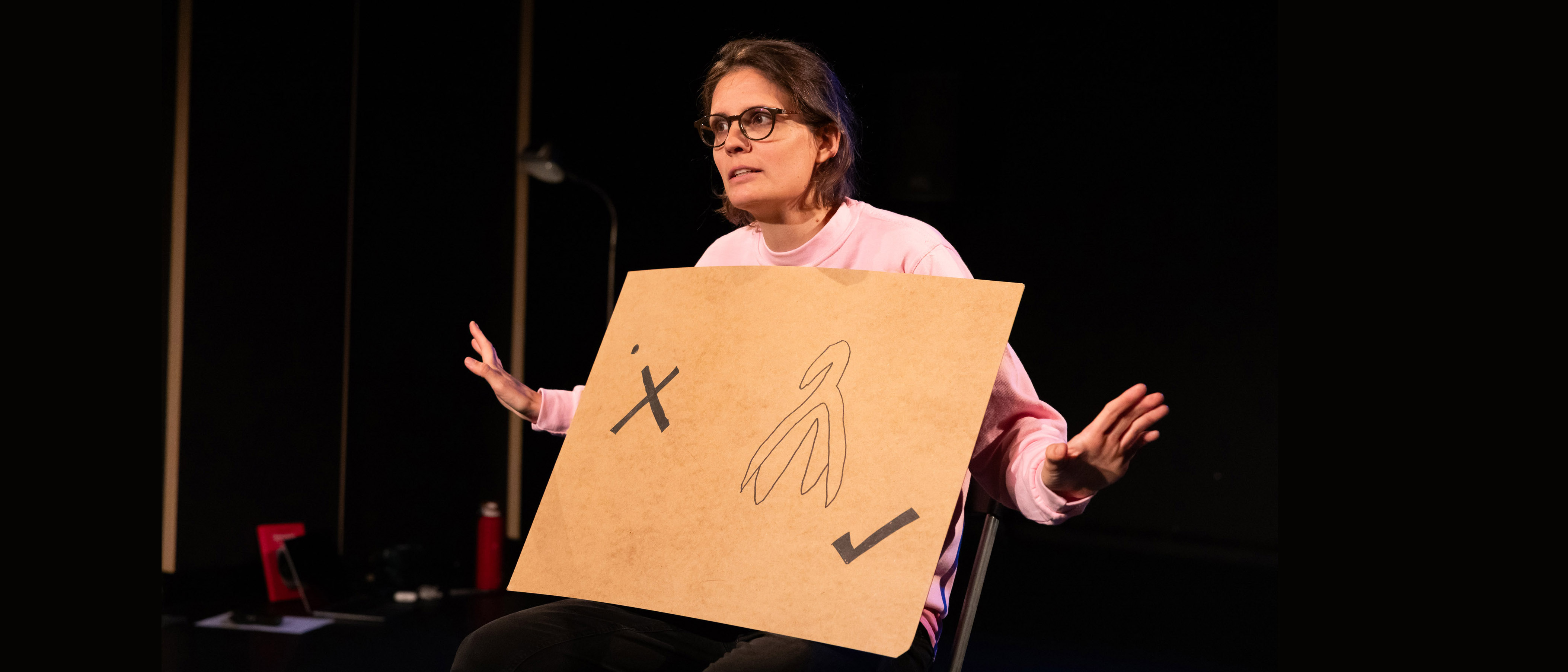

Catherine Malabou’s lecture The Clitoris is an Anarchist at the City of Women festival broached a topic that weaved through many of the festival events. In addition to her lecture, which is based on the book Pleasure Erased. The Clitoris Unthought, the clitoris also appears in Jasna Jasna Žmak’s performance this is my truth, tell me yours, in which the performer explains that the clitoris, in spite of what many people still mistakenly believe, is not just a dot or a hole in the body, but rather an autonomous, wholesome organ. The first part of Sex Education II by Tjaša Črnigoj is devoted to vaginismus, or painful penetrative heterosexual intercourse, likewise addressing the issue of female pleasure and the clitoris. It is no coincidence that the clitoris also appears in Archeology of Resistance in the Škuc Gallery, where one of the artists, Hristina Ivanoska, makes a direct reference to Catherine Malabou in her work.

Talking about the clitoris, which is still understood as the female sex organ, however, can easily become a slippery slope, which Malabou is mindful of. It is easy to get entangled in essentialism and biologism, which is why Malabou emphasises that she is not a trans-exclusionary radical feminist (or TERF) at the very beginning of both her book and her lecture, but rather that she seeks to disentangle the clitoris from being bound to a bodily organ defining women. She is endeavouring to understand the clitoris beyond the bounds of biology and binarity or sexual difference. She perceives it as an energy, a type of pleasure, a way of acting, meaning that she expands its meaning to include the social construct of gender. For Malabou, the clitoris becomes a name for a libidinal disposition that does not necessarily belong to a cis woman and can be found anywhere on the body, thus making it a sex organ that is not female by definition. The plasticity of the clitoris always resists domination and its inherent abuse, while also emitting rebellious, anarchist energy.

The issue of the clitoris thus becomes an intersection of the different waves of feminism, a non-hierarchical sedimentation of different past and contemporary (trans)feminist theories. Malabou’s question is how to think about the history of feminist struggles combined with transfeminist movements – namely, how to understand the second and third waves of feminism as they cross paths with the context of contemporary times. Malabou wishes to put feminism in dialogue with itself. As we are reminded in Sex Education II: Fight and in Agnès Varda’s film One Sings, the Other Doesn’t, both of which originate from or relate to second-wave feminism, reproductive rights are not to be taken for granted. Likewise, sexuality, pleasure, abortion and contraception accessibility are all political topics, while violence in these areas is institutional and systemic. The issues of second-wave feminism, which mostly centre around the experiences of cis women, are still relevant, but they are also intertwined with third-wave feminism associated with queer theories. It is important to understand that the struggle for transgender self-determination, fighting against the gender binary and against traditional family structures, is not an individualistic or identity struggle. It is rather political and economic, as it dismantles traditional family structures and the free reproductive labour that is inscribed in them, while simultaneously being fluid enough to evade unambiguous definitions, which would enable regulation, control, and the predictability of human desires, needs, and pleasure under capitalism. This makes it all the more important to stress the importance of the film Gabi, Between Ages 8 and 13 (Engeli Broberg) and the performance Atlas da boca (Gaya de Medeiros), which both shine light on the experiences of a transgender body, or rather the experience of being trapped in the binary and heteronormative social patterns we are raised in. At the festival’s intersection of these two waves of feminism, there was also a fourth, prompted by the #metoo campaign, expanding the notion and practice of consent and raising women’s awareness of sexual violence in the workplace, in culture, at universities, in nightlife and in everyday life. It surfaced during the festival both in Jasna Jasna Žmak’s performance of a lesbian who confronts the heteronormative ego of Marko Mandić and in the performance A World Without Women (Svet bez žena) by Maja Pelević and Olga Dimitrijević, where the artists draw attention to gender inequality in theatre by intertwining the documentary and the personal. What could almost be the festival’s opening lecture on the clitoris can thus be understood as a springboard to understanding feminism intersectionality, which is something the City of Women association continually encourages and raises awareness of, and which binds diverse films, exhibitions and performances into a multifaceted whole.