Archeology of Resistance

In her 2021 book Feminist Antifascism: Counterpublics of the Common, Ewa Majewska introduces the term ‘weak resistance’, which stands against the heroic narratives of revolutionary struggles that have filled the progressive imaginary for three hundred years. She brushes off the dogmatic air of an obsolete proposal formulated when the imagined actors of historical change were solely able-bodied, (mostly) white, cis men. Taking the Black Protests in Poland and the global International Women’s Strike as a starting point, Majewska describes the non-heroic strategies that “activated several layers of society, involving street demonstrations, actions on social media, artistic work, strikes, a refusal to fulfil housework duties, artistic actions, legal investiga- tions, and new law proposals”1 that made these protests stand out as well as enable massive global participation.

Similarly, Erica Chenoweth and Maria J. Stephan, the authors of the widely acclaimed Why Civil Resistance Works: The Strategic Logic of Nonviolent Conflict, pinpoint mass participation as a decisive advantage in the success of political campaigns. Based on empirical data, collected on a global scale spanning the entirety of the 20th century, the book argues that nonviolent campaigns enable participation of a broader social stratum, involving a par- ticipant base more diverse than the able-bodied, often cis male participants of violent struggles, thus permitting a greater variety of resistance strategies. The research seemed to suggest that mass support stands for, among other things, a variety of genders participating, which was later tested when Chenoweth and her research team included variables for gender in the data set (the scope of data collected is global and collecting began in 1945)2 Some of the more concerning findings of this new data set are that, in the aftermath of unsuccessful campaigns with a prominent positive focus on gender equality and significant participation of women (be they insurrections or nonviolent struggles), there is a decline in indicators for gender equality.3 So, it seems that the claims for equality tend to backfire with a conservative, patriarchal counter-response, which makes it even more vital for progressive, feminist, mass, and gender-equal resistances to succeed.

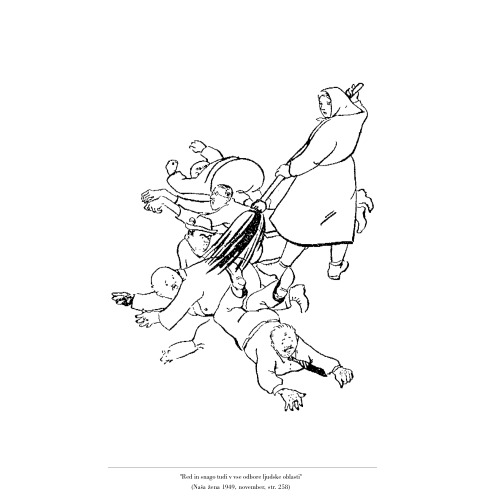

Returning now to the concept of weak resistance, in Feminist An- tifascism, Majewska makes a poignant introduction to the Soli- darność movement from the 1980s. She reminds us of how it was initiated in solidarity with Anna Walentynowicz, a female crane operator from the Gdansk shipyard who was laid off for protesting raising food prices, and that it was populated by many significant women through time. Nevertheless, the movement would probably be an outlier in Chenoweth’s gender equality data set. Convention- ally understood as a successful historical movement with a major participation of women, Solidarność did not bring long-term gender equality to Poland. On the contrary, its contemporary leadership supports the most regressive policies of the Polish government, like extreme cuts to reproductive rights. The (symbolic) erasure of women went so far that the leadership protested against the use of the Solidarność sign in recent feminist4 protests as well as its use in the art project titled Invisible Women of Solidarity by artist Sanja Iveković. Iveković created a piece in which she, in addition to introducing real women who inspired, organised, and participated in the Polish Solidarność movement, also substituted the image of an abstract man on a poster placed in front of the movement’s logo with a woman.5

The decline of reproductive rights, availability of social services, and economic standards of the general population in the post-socialist context go hand in hand with the symbolic erasure of women who fought for gender and social equality during socialism. Struggles initiated, populated, and led by women (from women in the anti- fascist struggle during WWII, women combatants in anti-colonial struggles and everyday struggles of people on the move, women and LGBT+ people in public space) need to be recorded and repeated for history. Women have and will create their own destiny through numerous acts of refusal, defiance, and other forms of weak resistance, as well as by participating in violent struggle, all off which is shown by the contributions in the program Archeology of Resistance: Corrective for the Future, part of the 29th edition of the City of Women Festival.

In the article “Critical Feminism in the Archives”, Marika Cifor and Stacy Wood write about the relevance of archives for social movements as a way of bringing attention to omitted persons, concepts, and narratives. Feminist art engages with feminist politics, and a great deal of archival work (in the broader sense of the word – as contributing to historicizing rather than neces- sarily adding material to existing or creating new public or private archives) has been done through research-based and documen- tary practices by contemporary artists. The exhibition in the Škuc Gallery brings works by Katia Kameli, Monica de Miranda, Barbara Blasin, Hristina Ivanoska, (and Zuzanna Hertzberg in Mala galerija), who research historical figures/movements/media and bring them to public attention. Works by Alicia Grullon and the SIDE collective, as well as the augmented reality walk by Amelia Gutiérrez, invent strategies to intervene in contemporary reality. In her book The Archival Turn in Feminism, Kate Eichorn proclaims that “contempo- rary feminism is as much about shoring up a younger generation’s legacy and honoring elders as it is about imagining and working to build possible worlds in the present and for the future”6. The ret- rospective view with a future ordinated agenda is shared and re- verberates through the whole series of events that are part of the Archeology of Resistance: Corrective for the Future.

Iva Kovač